Calculation Cited by Company Amid Proxy Fight May Overstate Profits for Many Investors

By John Jannarone, Editor-in-Chief

Strong shareholder returns are perhaps the strongest defense a company can make against investor criticism. But before taking reported numbers at face value, it pays to do some homework.

Consider the case of chemical manufacturer Ashland Global Holdings, which is under pressure from 2.5% shareholder Cruiser Capital to make operational improvements and replace part of its board of directors. Among Cruiser’s complaints is the fact that Ashland declined to speak with respected chemical industry veterans Dr. Bill Joyce and Allen Spizzo, both of whom own significant stakes in Ashland. The two men are also part of the investment fund’s slate of four nominees to join the company’s board.

One of Ashland’s responses to Cruiser Capital was that the company has generated strong returns for its shareholders. In a statement dated October 25, Ashland said the “total stockholder return of Ashland, a component of the S&P 400, has outpaced that index in recent years.” The letter goes on to cite figures including a five-year total stockholder return of 73.6% versus 49.7% for the S&P 400. The company reiterated its purported outperformance again last week in a statement to Bloomberg.

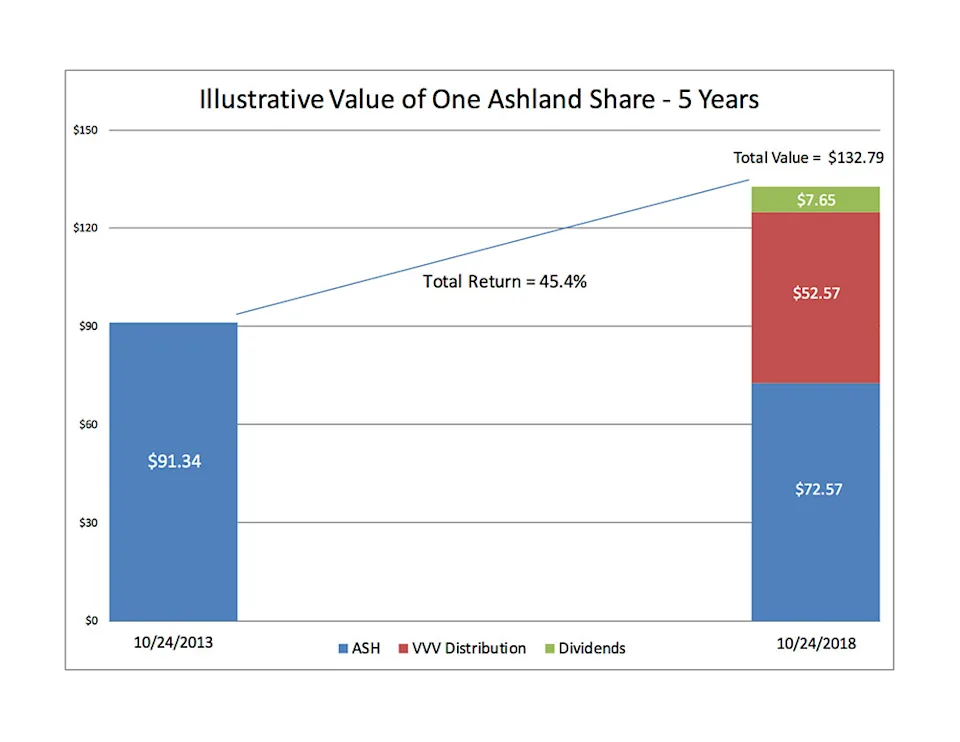

However, investors who bought and held may have seen far lower returns over that time period. Someone who bought a share of Ashland on October 24, 2013, would have invested $91.34, based on the closing price. Assuming no trades were made, that investment would have grown into three pieces: the value of one share of Ashland, the value of 2.745 shares of Valvoline that investors received as a distribution in May 2017, and dividends from both Valvoline and Ashland. The total on October 24, 2018, would be $132.79, indicating a return of 45.4%, according to calculations by CorpGov. That return is 28.2 percentage points below the 73.6% return Ashland cites in its statement.

What explains the gap? The key is that Ashland’s cited figure is the result of a mathematical formula with assumptions that may be unreasonable. In particular, the formula assumes that the spinoff of Valvoline in May 2017 was treated as a dividend that was immediately reinvested into Ashland shares. The company said in its latest annual report that the “effect of the final separation of Valvoline Inc. is reflected in the cumulative total return of Ashland Common Stock as a reinvested dividend.” CorpGov also confirmed that data providers including Capital IQ and Bloomberg use the same calculation for total shareholder return (TSR) that matches the company’s figures.

Normally, such a treatment of dividends has a modest effect on return metrics. But in the case of Ashland, the impact is significant. The reason is that at the time of the spinoff, the Valvoline share distribution was actually worth more than the remainder of Ashland itself – by a margin of 51% to 49%. As a result, the decision to pile back into Ashland effectively meant doubling down on the stock. According to an analysis of shareholder return data by CorpGov, investors are assumed to have reinvested in Ashland at a theoretical price of $59.57 on May 12, 2017. Since then, Ashland shares rose significantly – to $72.57 on October 24, 2018 – which explains the outsized returns in the company’s cited calculation.

Equally perplexing is the fact that investors simply could not have reinvested in Ashland at the reduced price of $59.57 on May 12 because the stock didn’t trade anywhere near that level. The shares in fact closed at $121.75 that day because they didn’t yet reflect the dividend. What’s more, it took a few days for any sale of Valvoline shares to settle and free up cash to reinvest. By then, Ashland shares were trading a few dollars higher and never fell back below $60.

Among the investors who didn’t enjoy the benefit of immediate reinvestment in Ashland are insiders at the company itself – including CEO William Wulfsohn. No board directors have bought more shares of Ashland through the open market since the spinoff, according to public filings.

In a statement to CorpGov, an Ashland spokesman said “Ashland’s calculation of total shareholder return assumes reinvestment of dividends. This is a standard, well-accepted approach within the financial community. Of note, the underlying returns of the S&P MidCap 400 that Ashland references as a benchmark utilize this same methodology, providing for an ‘apples-to-apples’ comparison.”

Of course, investors who bought one share on October 24, 2013 and have held both Ashland and Valvoline would have received dividends totaling $7.65 per share – all of which could have been invested somewhere. Generously assuming a 30% return on those dividends, the total five-year return would have been 47.9%. That’s still short of the S&P 400 return of 49.7%% and well below the return of 68.04% in the S&P 500 (the latter index is worthy of mention because the company said about a year ago it was utilizing the S&P 500 as its peer performance group for compensation purposes).

Tracking the details of Ashland’s returns is problematic for regular investors without access to detailed data. Publicly-available sources such as Yahoo Finance don’t even publish the pre-spinoff prices at actual historical levels – only those that have been adjusted for the transaction.

Given that Ashland’s returns may not be as impressive as they initially appear, it could be more difficult for the company to brush off criticism from an activist shareholder. It is particularly surprising that the company declined to speak to Dr. Joyce, the former CEO of Union Carbide, now a unit of DowDuPont. Dr. Joyce was also the CEO of Hercules, which Ashland acquired in 2008. Ashland has also declined to speak to Mr. Spizzo, former CFO of Hercules, who is on the board of specialty chemical company Ferro Corp.

Ignoring potential input from Messrs. Spizzo and Joyce is troubling because the assets of Hercules now comprise a significant part of Ashland. And that business division, Ashland Specialty Ingredients (ASI), has struggled for the last several years. ASI’s adjusted Ebitda margin target of 25% to 27% has been in place since at least 2014 – just before Mr. Wulfsohn took the helm as CEO. But the unit’s margin has held well below that level from 23.3% in 2015 to 23.2% in 2018. Growth in adjusted Ebitda has also been sluggish over that timeframe.

It’s not the first time an investor noticed problems in Ashland’s ASI group. Elmrox Investment Group, which spoke to The Wall Street Journal in January 2016, also argued that operational improvements were needed. In an August 2016 letter reviewed by CorpGov, Daniel Lawrence, who was then Managing Partner at Elmrox, said he was confident that ASI’s Ebitda margin could rise above 30%.

Prior to Elmrox, Jana Partners took a stake in Ashland in 2013. Like the two activists that followed, Jana’s strategy included operational improvements at Ashland.

Ashland also continues to trade at a discount to peers. The company has an enterprise value, adjusted for debt, of 10.1 times fiscal 2019 consensus earnings, according to FactSet. That compares with forward multiples of 17 times for Balchem, 12.1 times for Sensient Technologies, and 16 times for Croda International.

To be sure, Ashland’s stock has had a recent stretch of strong performance since the Valvoline spin. But much of that happened since Cruiser Capital made its presence public a year ago and suggested the company place former Sealed Air CEO Jerome Peribere on the board (which the company did). By contrast, Ashland gained just 5%, including dividends, from the time Mr. Wulfsohn became CEO up until the day before the Valvoline spin in May 2017.

It is likely that many shareholders, particularly those without access to expensive data, would never have known the full story behind Ashland’s shareholder returns. In this case, the presence of an activist should prompt investors to dig a little deeper.

Contact:

John Jannarone, Editor-in-Chief

www.CorpGov.com

Twitter: @CorpGovernor